Warren Buffett is probably the most successful investor ever, and has consistently achieved high returns for decades, but even Buffett is not perfect. In recent years, he has received quite a few wrong decisions that cost him tens of billions of dollars in losses. Where was Buffett wrong and how can you do it right?

Warren Buffett is considered the most successful investor of all time. The 88-year-old man named “The Oracle of Omaha”, after his home town in Nebraska, has more than $80 billion in capital, which he has accumulated in various successful investments throughout his life. The stock portfolio of his investment company – Berkshire Hathaway, has averaged more than 20% a year, so if you invested $100 in the company’s shares in its 1965 founding, they were worth about $2 million today.

But in recent years it seems that Buffett has a hard time beating the markets. On the one hand, of course, it’s hard to beat the indices when you manage hundreds of billions of dollars, and Buffett has referred to this several times in recent years. On the other hand, it appears that his investment strategy, which has been consistent for decades, has undergone several changes that did not necessarily improve the return his portfolio presents. Fortunately, Buffett has no problem admitting his failures and mistakes, so we can learn from this and correct our own ways.

It’s hard to choose a single winning technology company

For decades, Buffett has been careful to invest in old-fashioned companies such as industrial companies, insurance, finance, energy and basic consumer goods. He stayed away from technological companies on the grounds that it is very difficult to assess their success in the distant future.

Buffett deviated from this practice when Berkshire Hathaway purchased IBM shares valued at $10.7 billion in 2011. Despite the decline in IBM’s financial results over the years, Buffett continued to hold the stock until in 2018 he admitted his mistake and sold all his holdings in the company. One of the reasons for IBM’s decline was the rapid transition of many customers from the use of old information technology, which was one of IBM’s strengths, to cloud-based technology, and IBM was not smart enough to enter this field in time and lost revenue. No one can predict such technological changes, which is precisely why Buffett has distanced himself from investing in technology companies over the years.

Surprisingly, at the same time as the sale of IBM shares, Buffett has further increased his investment in another kind-of technological company – Apple, which now accounts for about one-fifth of Berkshire’s portfolio. As in the case of IBM, Apple shares as well were bought on the basis of its market leadership in recent years and attractive valuation relative to competitors. However, recently Apple was also unable to restore the growth rates that characterized it in the past due to increased competition with Chinese manufacturer and excessive pricing of its new products, without presenting a sufficient technological breakthrough. Without growth, Apple’s 15 price to earnings multiplier is probably not particularly cheap, and perhaps Buffett understood this, and this is why he reduced his position in Apple by about 1% in the last quarter.

Buffett also bought shares worth $2.1 billion of Oracle, and surprisingly sold them after just one quarter. He said he did not know the company’s activity well enough. Buffett apparently has not yet learned the lesson, since he has sinned in technology again in the last quarter, buying $730 million worth of shares of Red Hat…

Thus, when Warren Buffett decides to leave his comfort zone to the technology industry, it is probably best to take it with a grain of salt.

“Never lose money”

Much has been written about Warren Buffett’s investment strategy. He is credited for saying that the first rule in investments is: “Never lose money,” and the second rule is “Don’t forget rule No. 1”. Buffett’s intention is to acquire companies with a sufficiently large margin of safety to protect you from your valuation mistakes (or uncertainties), which is based on the company’s future cash flow forecast. In an investment in Kraft-Heinz, for example, Buffett did not follow his own rules.

In 2013, Buffett joined the Brazilian corporation 3G Capital to acquire control of Heinz, and in 2015 they accounted for a significant portion of the $49 billion merger deal with Kraft. Kraft-Heinz became the third largest food corporation in North America. Buffett had more than 300 million shares at the time, and shortly after the merger, they were worth more than $30 billion. Since then, the share value has deteriorated in line with the weakening of the company’s operations and the write-offs of some of its intangible assets, and Berkshire Hathaway’s holding in the company has been cut by more than half. Referring to this, Warren Buffett said that he made a mistake and bought his holdings in the company at too high price, which cost him a loss of a lot of money so far.

One of the mistakes of the Kraft-Heinz administration was that it did not internalize consumers’ transition to healthier food, and continued to market the Macaroni-cheese and other old products that a growing portion of the public no longer wants. Although the price of the share seems much cheaper today than in the past, if the company does not make a real revolution in its products in the coming years, it will continue to fade and Buffett will lose more money on this investment.

What is the right time to sell a stock?

According to Buffett, “the best time to sell a stock is never,” and Buffett is known to hold shares for years, sometimes even decades. Is it smart? Not always.

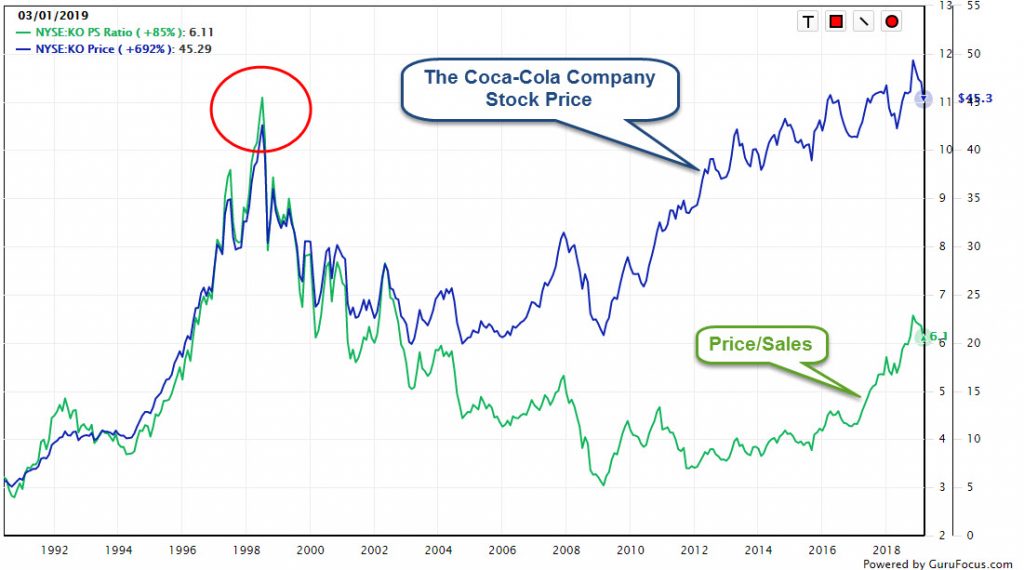

One of Buffett’s oldest and most significant holdings is in Coca-Cola shares, which is still over 10% of Berkshire’s portfolio. The stock is one of Buffett’s most successful investments – he bought it for the first time in 1988 for about $2.5, and in 1998 it jumped to a record $42.6, but since then its price has fallen continuously until in 2004 it reached a low of half of the peak. After that, the stock recovered, but it took about 20 years for the stock to return to the record price of 1998. Today it trades at $44.8, meaning that Buffett, who did not sell any Coca-Cola shares all the way, earned only 5% on this investment in 21 years.

Taking into account the dividends distributed by the company, this is an average dividend yield of about 3% a year. This is a nice return, but in 1998 it was possible to buy ten-year US government bonds at a yield to maturity of 5.5% and after the redemption in 2008 to replace it with new bonds at a yield of 4%, so that the dividend yield Coca-Cola itself did not justify the continued holding of the share.

In 1998, when Coca-Cola reached its peak, the company traded at a Price to Sales multiple of 5.1, much higher than the reasonable valuation for a mature company like Coca-Cola. For the sake of comparison, Facebook is currently trading at a sales multiple of 8.6, a pretty high value in itself, but Facebook is growing about 50 percent a year, compared with Coca-Cola, which in those years grew only 2 percent a year.

Therefore, the time to sell a share, including Coca-Cola, is not “Never”, but at the time when it reaches its fair value. It makes no sense to keep a stock traded at higher prices than it is actually worth, and certainly not in the modern era where stock price volatility is much higher than it was in the previous century. If Buffett had followed this rule, he probably would have sold the share as early as 1996-1997 and lost part of the return it had produced until 1998, but he had decades of using the money to buy better stocks that would yield a much higher return instead of.

When Buffett invests in what he understands, it is worth listening

Berkshire Hathaway is a huge company that manages hundreds of billions of dollars, so the mistakes that Buffett makes from time to time cause huge damage. Despite that, Warren Buffett is still one of the smartest investors in the world, so it is worth to keep being updated on his activities.

In recent quarters, Buffett has returned to invest in a field he knows well and has invested in the past – banking and finance. Among Buffett’s 10 largest holdings are several banking corporations in which the company holds tens of billions of dollars worth of shares, such as Bank of America (BAC), Wells Fargo (WFC), JPMorgan (JPM) and Goldman Sachs (GS). The largest banks in the United States are more financially stable than ever, their ability to expand net interest margins increased as a result of the interest rate hikes in the country, and their shares are traded at convenient valuation. Thus, Bank stocks looks like quality investments that will be a source of high returns for Buffett in the coming years.

2 Comments on "Learn from Buffett’s mistakes: Four golden rules of Investing"